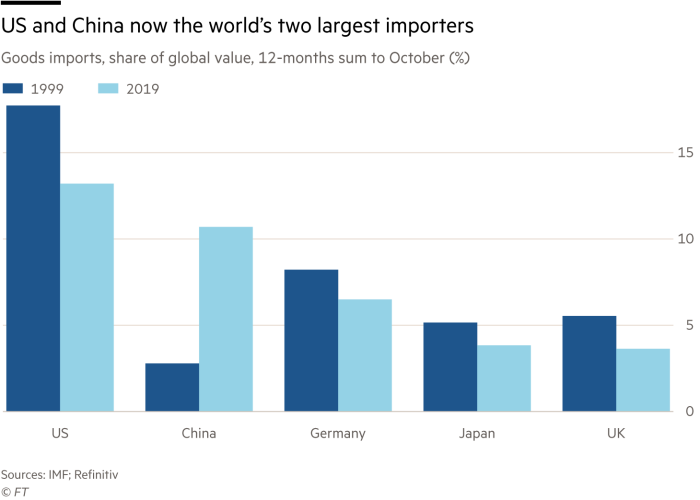

In the years since China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, the country’s economy has grown to become second only to the United States in purchasing power parity terms. In the past decade, its global trade influence has also spread, and China has gradually usurped the US as the major supplier of goods to Europe, Asia, Africa and South America.

As long as it operated as a cheap factory, China’s growth was welcomed by the US, and its emergence as a new market for consumer goods was eagerly anticipated. However, in the mid-2010s — possibly provoked by China’s covert military expansion into the South China Sea and its expansive Belt and Road Initiative, as well as an ambitious plan to move up the value chain outlined in 2015 — the relationship between the rising nation and the incumbent superpower became more competitive.

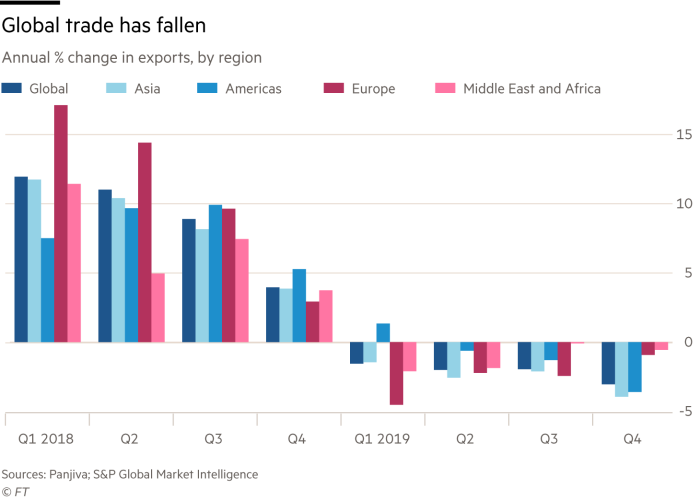

With the election in 2016 of Donald Trump on an “America First” platform, the gloves came off. Unhappy with the trade imbalance, the US president kicked off a trade war in 2018, imposing tariffs in two waves to encompass around $400bn worth of goods shipped between the US and China. The fallout for companies has been considerable.

This new, more combative relationship has changed the global commercial landscape, disrupting supply chains — most noticeably, perhaps, in the technology sector. It has arguably accelerated a trend that was already under way, giving China an incentive to develop its own standards and achieve self-reliance in critical strategic sectors, including high tech. Perhaps the most significant consequence of this is the potential for a longer-term decoupling of China and the US, and the emergence of two rival and separate spheres of influence, in both trade and technology.

The coronavirus outbreak, which emerged in Wuhan in December 2019, shutting down China’s economy for an extended period, has served to highlight the likely consequences of a dislocation of the world’s two largest economies.

On January 28 2020, the FT Future Forum Think Tank brought FT commentators and China experts together with companies representing sectors from retail to law to discuss these developing challenges. In this report, we discuss the impact of the US-China trade war and the implications for European and British companies.

The short-term implications

1. Trade diversion — the US is buying things from places other than China. This is a small positive for the EU and UK.

In early 2019, the National Bureau of Economics estimated that as much as $165bn of trade would have to be rerouted per year to avoid even the tariffs in place at the end of 2018.

Now in its second year, the trade war has indeed siphoned orders away from China and the US to alternative suppliers. It is not only cheap suppliers in Asia that have benefited. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development has shown that the EU, together with Taiwan, Mexico and Vietnam, has picked up some of the crumbs. As China’s exports declined by around $25bn in the first half of 2019, the EU exported an additional $2.7bn to the US, with the highest proportion of that in machineries sectors.

Even if this might mean that China loses out, the result is not an outright win for the US either. An economic model co-authored by Robert Zymek, lecturer at the University of Edinburgh and a Future Forum attendee, anticipates that improvements in the US trade deficit with China will be almost entirely offset by declines in the American position relative to its other trading partners. This invites the question whether the US will simply watch its other trade balances worsen without taking action?

Future Forum attendee Gordon Cheung, an associate professor at Durham University, observes that there are more Chinese students in UK universities. “[T]he general impression is that the numbers have gone up greatly.” He notes that this may not be sustainable should relations between the US and China normalise.

2. The “phase one” trade deal — China has committed to buying $200bn more in goods from the US across sectors including agriculture, services, manufacturing and energy. This is potentially negative for the EU and UK.

Any increase in Chinese purchases from the US is unlikely to be new buying, so it will have to be diverted from somewhere else. Matthew Rous, chief executive of the China-Britain Business Council, who also attended the Forum, is looking on the bright side. He notes that the ceasefire signalled by the “phase one” trade agreement reached by the US and China in January removes the risk of UK companies being affected by any imposition of new American controls on products containing Chinese-made components.

He also contends that “the Chinese promise to encourage more agricultural imports from the US by bringing regulations on farm produce more closely in line with WTO rules and standards benefit American and non-American producers alike”. Bear in mind, however, that China will have to ditch existing trading partners such as Argentina and Brazil in order to satisfy this US condition, and that would not be easy.

A more likely outcome is that the coronavirus outbreak allows China to delay implementation of this aspect of the deal — or even to renegotiate it. The US presidential election in November adds to the uncertainty: even a second term for Mr Trump is no guarantee that the terms of the deal will not be changed.

3. The coronavirus — while not directly related to the trade war, it has exacerbated the estrangement between the US and China. Supply chains have been thrown into disarray. Several international airlines have temporarily shut down their routes to China and many others have slashed their capacity to Asian destinations. Everyone loses.

Virus-induced embargoes have put a strain on many high-profile companies, from those that sell in China to those that manufacture there.

Wuhan, the city most affected by the outbreak, is a centre for car parts, so automakers have been hit particularly hard. Just a few weeks into the crisis, Volkswagen shut its plants in China and other global carmakers warned that European and US based facilities were also just weeks away from closures.

Problems for the companies mean problems for their financiers, too. Adam Shepperson, head of trade origination and structuring at Santander, stresses concerns around “extended supply chains in the industrial and manufacturing space”. Here, cancellation of orders and resultant factory shutdowns can imperil “business models and ultimately client creditworthiness”.

The medium-term outlook

1. Switching suppliers — as the trade war has dragged on, companies have had to consider finding alternative sources of inputs for their production chains. Less simple than buying completed goods from new vendors, switching to new component suppliers comes with friction costs as well as, potentially, higher prices. Trust, quality assurance and logistical networks all have to be rebuilt. The chain is not well oiled, at least to start with. Manufacturers lose.

For reasons including politics and commercial sensitivities, few companies are prepared to share what they have been doing to restructure their sourcing. But consider Li & Fung, a Hong Kong-based sourcing agent, which revealed in its 2019 interim results that it had helped one US retailer move reduce its reliance on Chinese inputs from 70 per cent to 20 per cent over two years, with plans for another to go from 40 per cent to 10 per cent by 2020, outsourcing to at least seven other economies.

Not all companies are moving that quickly. A September 2019 survey carried out by the EU Chamber of Commerce in China noted that just 10 per cent of respondents had changed suppliers, although this number had risen from 6 per cent in a January 2019 survey. One company admitted that its reliance on China was “dangerous”.

As recently as January 2020, Citi’s Financial Strategy and Solutions Group also noted that one-third of western European companies in the global MSCI index have “meaningful China trade risk exposure driven by larger manufacturing activity”.

The coronavirus outbreak has provided a stark illustration of how reliant many companies still are on China. For those that have hesitated, and are resilient enough to survive, it may finally provide the necessary impetus for supply chain diversification.

2. Uncertainty paralysis — investment decisions are increasingly on hold as companies cannot predict what happens next in the trade war. Another broadly negative situation.

The World Uncertainty Index, which tracks uncertainty around the globe, shows that the condition is rampant worldwide. The measure, based on the frequency of the word “uncertain” in Economist Intelligence Unit reports for over 140 countries, spiked in the fourth quarter of 2019.

As usual in such an environment, companies are trying to do as little as possible. In May 2019, one-third of respondents to an AmCham China survey said that they had delayed or cancelled their investment decisions, more than in a similar survey taken the year before.

The September 2019 EUCham survey also noted that there was a strikingly high level of paralysis: nearly two-thirds of respondents said that they had left their strategies unchanged but were “monitoring the situation”. Compared to a previous questionnaire in January, a higher proportion were taking steps to adapt to the trade war — partly accounted for by the 15 per cent who said they had delayed investment and expansion decisions.

Uncertainty surrounding US policy does not help. During the Future Forum panel discussion, the FT’s Martin Wolf noted that even the Americans don’t seem to have decided what they want. Mr Wolf said that the phase one trade deal came “in the context of America going through a massive rethink in its relations with China, and it hasn’t made its mind up yet”. Worse, the deal itself is not fixed, given that it allows Mr Trump to retaliate if he does not like the way the Chinese implement the agreed terms.

3. The phase one trade deal — this has secured some gains for EU and British companies. Laws which focus on fairer treatment of foreigners, open up some of the financial sector to foreign investment and put in place protections for intellectual property are good for Britain’s financial sector, and both EU and British creative and design industries.

The US has been vocal about its commercial losses due to China’s “economic aggression”. The White House has estimated that intellectual property theft costs the US between $225bn and $600bn a year. No wonder then that it has been pushing China to address the issue.

The phase one deal extracted concessions on the treatment of foreign interests in China. Forced technology transfers have been outlawed, ownership limits on pension management and life insurance enterprises have been relaxed. Britain, in particular, still thrashing out the terms of its departure from the EU, should welcome the opportunities this presents — assuming that China enforces the new laws.

The long term view

The conflict between the US and China is not simply economic — it has political, cultural and military dimensions. For these reasons it is unpredictable and is unlikely to dissipate any time soon. The greatest risk over the longer term is that the US and China split into two spheres of influence, one servicing the US and abiding by its standards — from technology to governance — and another centred around China. As the charts tracking the change in trade dependency shows, the likelihood is that China’s sphere will be larger and incorporate the lion’s share of global growth potential. Will those caught in the middle, including companies in the EU and Britain, be able to operate in both?

1. Manufacturing capacity shifts — this is tougher and involves even more cost than moving sourcing, requiring new factories and workers. Even if they are able to relocate facilities, it is not a given that companies would be able to use their non-Chinese Asian capacity to service the US sphere, should two distinct trading blocs develop. Localising operations in each of the US and Chinese spheres also may not solve the problem due to conflicting laws, loss of control or property and difficulties in repatriating profits.

In December 2018, Paul Maidment, adviser to Oxford Analytica, noted in the Harvard Business Review that companies were starting to move their production facilities. Now, he says, if you want to find a textile or factory worker in Vietnam, “bad luck”. Capacity in this first choice for relocation is already constrained.

An executive from an Asian sourcing company agrees that the easy wins have already been achieved: “Buckets, plastic pots and so on are hard to move because injection moulding equipment is not easily relocated.” As for textile factories, even Vietnam still needs to import the fabric from China, since it does not have the necessary mills. This only superficially circumvents country of origin issues and arguably does not meaningfully reduce reliance on China.

Meanwhile, China is being more strategic about which parts of the supply chain it gives up. AmCham points out that companies in Shenzhen, which have tended to dominate production of technology outsourced from the US, may farm out lower-end assembly to neighbouring countries while holding on to higher value processes. And, as with Vietnam and textiles, China provides many of the components required by the end-product. It is striking that Vietnam has overtaken Germany as China’s fifth largest export partner.

The chances of such production capacity returning to the west, certainly in the near term, are slim. Mr Maidment points to comments from Tim Cook, chief executive of Apple, that production engineers in China could fill several football fields, but barely a room in the US. On the upside, moving production to new countries could both put producers nearer to fast-growing markets and help to develop more backward economies, even if this is some way off. “Thailand is well established for outsourced manufacturing. But Laos or Cambodia? The regulations and legal infrastructure, human capital . . . not there”, Mr Maidment observes.

Nonetheless, Mr Shepperson notes that given the longer term risk of a decoupling of the US and China, “it is critical that commercial counterparties retain optionality” and have strategies in place to cope with future change.

2. Technology divorce — makers of technology products in the US and China are increasingly barred from using each other’s products on “national security” grounds. China plans to rip foreign technology out of state offices by 2023. The US has barred government agencies from buying equipment from certain Chinese suppliers including Huawei and Hikvision. The UK has already fallen foul of the US for allowing Huawei a limited role in its 5G rollout.

The ban has been bad for vendors of US technology into China, but has also left the EU and Britain, and their companies, in a tricky position — as illustrated by the diplomatic fallout from the UK’s Huawei decision.

At the very least, US moves to put China behind a firewall are likely to accelerate the latter’s quest to develop its own technology standards. It also makes the self-sufficiency identified as an overarching policy aim in the “Made in China 2025” plan a far more pressing need. The Council on Foreign Relations notes that the plan targets 70 per cent self-sufficiency in high tech industries by 2025 and a dominant position in global markets by 2049, through methods including use of subsidies, acquisitions and tech transfers.

In a 2017 analysis of China’s ambitions, the EU chamber of commerce in China noted that the Chinese press had reported RMB2tn in funds gathered in 2015 to support the effort. Its advice to European companies looking to cope with the challenge includes aligning themselves with China’s long-term goals, continuous innovation, identification of emerging competition by monitoring international mergers and acquisitions and diversification of markets and clients.

This may not be easy, but it is imperative for survival. “The existential threat”, says Mr Maidment, is that “China becomes technologically innovative on top of its production and engineering expertise, but the US, while it can still design, cannot recover its lost production and manufacturing skills. Then the west becomes dependent on China rather than China being dependent on the west.” The US’s policies appear to be accelerating this trend.

3. The tech divide cements the economic divide into two spheres — Dr Yu Jie, senior research fellow on China at Chatham House, noted on the Future Forum panel that China wants to assert what she termed the “discourse of power”, not only developing and acquiring technology but setting standards. She suggested that China might make it a condition of market access that international companies adhere to these standards.

Trying to operate across two distinct spheres could become as impossible as using a Betamax cassette in a VHS video player used to be. The Balkanisation of technology systems from hardware to software could exacerbate the difficulties of operating between jurisdictions if electronic communications, for instance, are not standardised.

Anyone who has tried to use Google in China has already encountered this challenge.

Without a united front, navigating the middle ground between China, whose money is needed for investment, and the US, the traditional ally whose clout is relied on for defence, will be difficult for companies in Europe. This is especially the case for post-Brexit Britain. As already noted, it has clashed with the US over Huawei, although given the existing telecommunications infrastructure, there was no cheap alternative.

British companies may pay the price. Many representatives of businesses at the Forum said they felt themselves to be in an invidious position.

Conclusion

There is an outside chance that China and the US will “re-couple”. The economic damage wreaked by the coronavirus might make the global community pull together. It may also, as commentators including the FT’s Jamil Anderlini have posited, lead to regime change in China.

In similar vein, Martin Wolf pointed out on the Forum panel that Robert Lighthizer, the US trade representative, supports a strategy designed to “break open China”, as he did with Japan in the 1980s. He is backed by a vocal lobby in the US, with organisations such as Tariffs Hurt the Heartland publicising the costs of the trade war borne by US consumers.

But this position is not shared by Mr Trump, who wants trade rebalanced and may well get re-elected in November, nor by national security hawks, who warn of China’s infiltration into US systems and may hold sway even under a Democratic president. The more likely outcome is that the US ends up being contained by its own efforts to contain China, boxing in its allies along with it.

The FT Future Forum is an authoritative space for businesses to share ideas, build relationships and develop solutions to future challenges. The Future Forum set up the think-tank to make the most of the expertise of our member companies. The Future Forum think-tank is funded by foundation partners. Its reports are editorially independent.

Source: Economy - ft.com