FT subscribers can click here to receive Brexit Briefing every day by email.

The British government’s threat to walk away from Brexit trade talks with the EU, if the two sides make little progress by June, rests on a mixture of domestic political calculations, ideological itches and commercial reasoning.

In terms of domestic politics, Prime Minister Boris Johnson and his ruling Conservatives want to consolidate the popular support they amassed in the December 12 general election, chiefly at the expense of the opposition Labour party.

This will entail large-scale infrastructure investment programmes, aimed at rewarding voters who backed the Tories in less affluent parts of England, and an emphasis on immigration restrictions applied to EU citizens.

The ideological impulse revolves around the idea of building closer relationships with the English-speaking world: former settler colonies such as Australia, Canada and New Zealand; former imperial possessions such as India, Malaysia, Singapore and parts of Africa; and, outside the Victorian-era British empire, the US.

Rightwing Conservative circles regard such “Anglosphere” countries as more natural partners than continental Europeans for the UK.

The commercial reasoning is that, judged by economic performance, the EU is — in the Conservatives’ eyes — a moribund place, burdened with a malfunctioning currency union and suffused with a spirit of pettifogging protectionism.

How true is this claim?

Erik Nielsen, group chief economist at UniCredit, the Italian bank, estimates that, over the past 20 years, UK real gross domestic product growth has averaged 1.9 per cent, versus 1.8 per cent in Spain, 1.4 per cent in France and Germany and 0.4 per cent in Italy.

On the other hand, in per capita GDP terms, Germany has slightly outperformed the UK — 1.2 per cent versus 1.1 per cent.

More revealing are the chronically low levels of UK labour productivity. Output per hour worked is lower in the UK than in France, Germany, the Netherlands, Scandinavian countries and several other EU member states.

Lastly, UK economic growth in this period was driven to no small extent by borrowing abroad and the sale of business and property assets to foreigners, Mr Nielsen says.

Is the UK better than EU economies at exploiting cutting-edge technologies? Maybe not, according to the latest Bloomberg Innovation Index.

The UK does not make it into the top 10 of this index, which is headed by Germany and includes five other European countries — Switzerland, Sweden, Finland, Denmark and France — as well as South Korea, Singapore, Israel and the US.

Still, the Johnson government knows its mind. Newly liberated from the EU, the UK must diverge from its neighbours’ common rules and standards in order to maximise opportunities in trade and investment with the rest of the world, it says.

EU governments and British companies would be making a mistake if they did not take Mr Johnson’s government at its word on divergence.

After the government published its Brexit trade objectives, Allie Renison of the Institute of Directors, which groups British business executives, said: “For most IoD members, maintaining ease of trade with the [EU] single market is more important than being able to diverge from EU regulations.”

But her plea fell on deaf ears with Michael Gove, the Cabinet office minister who is Mr Johnson’s right-hand man on Brexit.

He confirmed this week that the government anticipated British businesses trading with the EU would have to hire up to 50,000 staff to do the new customs paperwork.

How this will improve UK labour productivity remains to be seen. But it is a price that the government clearly thinks British companies should pay, whether they like it or not.

Further reading

© FT Montage/Dreamstime

EU-UK trade talks: four key battle lines for post-Brexit settlement

The battle lines for talks on a post-Brexit settlement between Britain and the EU have been set, accompanied by a predictable opening salvo of cross-channel accusations ahead of negotiations that begin on Monday. “If Number 10’s vision of sovereignty means jumping off the cliff edge, no one will be able to stop Britain,” said one EU diplomat. “A no-deal would hurt Britain more than the EU.” (George Parker, FT)

Border red tape will mean 50,000 new form-fillers after Brexit

Michael Gove has endorsed claims that up to 50,000 people will have to be recruited to carry out customs paperwork under the government’s preferred Canada-style trade deal with the EU — the equivalent of the population of a medium-sized town. (George Parker and Daniel Thomas, FT)

Rishi Sunak should opt for masterly inactivity in his first UK Budget (Martin Wolf, FT)

Hard numbers

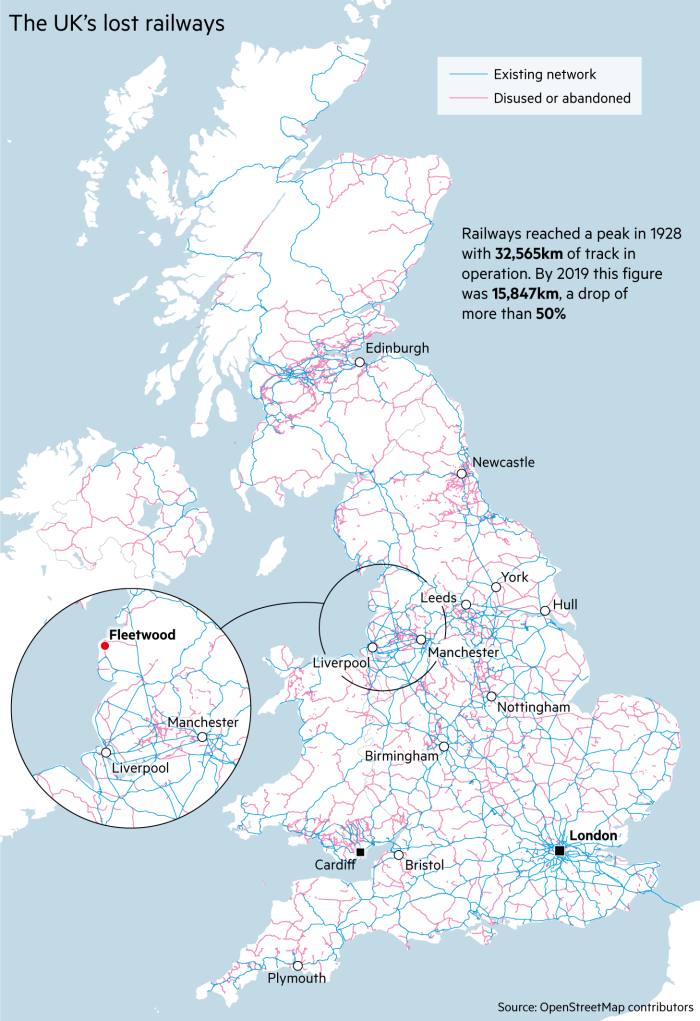

Matthew Engel: How Britain fell back in love with the railways.

On a Friday afternoon in November, in the midst of Britain’s election campaign, Boris Johnson appeared unannounced at the small-town railway station of Thornton-Cleveleys in Lancashire. He did not travel by train.

This coming May will mark the 50th anniversary of the last passengers arriving at Thornton-Cleveleys. It is 21 years since the last freight train trundled wearily through. Yet Johnson was here to say that, if he won the election, all that would change.

Source: Economy - ft.com