Investors are seeking more clarity from the US Federal Reserve this week on how much it may expand its balance sheet following the central bank’s efforts to restore order to short-term funding markets.

The Fed has been buying US Treasury bills at a rate of $60bn a month since a big jump in overnight borrowing costs last September and chairman Jay Powell is set to face sharp questions about how its actions are affecting markets on Wednesday.

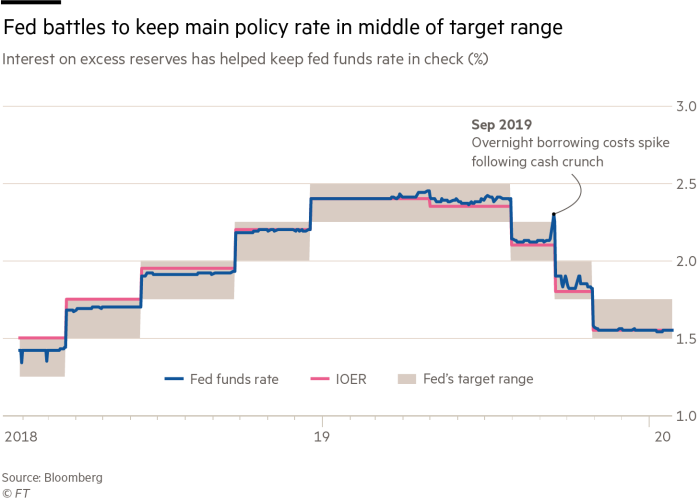

Mr Powell will speak at a regular press conference after the Federal Open Market Committee’s two-day meeting, which is expected to result in a tweak to a key tool it uses to implement monetary policy with US interest rates close to the bottom of the Fed’s target range.

He is likely to have to address criticism from some market participants that the Fed’s actions have been pushing up asset prices.

“What the market really wants is to know what the medium-term game is,” said Mark Cabana, head of US rates strategy at Bank of America.

After September’s leap in the overnight “repo” rate, policymakers concluded that they had gone too far in withdrawing their post-crisis stimulus, allowing banks’ excess reserves held at the Fed to fall too low.

The Fed reversed course and began expanding its balance sheet again by buying short-dated Treasury bills, crediting banks with reserves and driving up the level of cash in the system. It said the bill buying would continue into the second quarter of 2020 but declined to offer a level of bank reserves it would consider sufficient.

The level had fallen as low as $1.4tn in September; it is now at $1.6tn.

Since September, the Fed has also been intervening directly in the repo market. Originally it said those operations would continue until at least January, but Mr Powell and Richard Clarida, his vice-chairman, have more recently indicated they could continue until at least April.

“The Fed’s extremely aggressive response to the repo blowout in September, as well as their timidity in pulling back from that response . . . could be signalling to markets that this is a Fed with a very low tolerance for market fluctuations,” noted Blake Gwinn, head of front-end rates strategy for the Americas at NatWest Markets.

The turmoil in short-term funding markets reflects how the Fed, like other central banks, continues to wrestle with how to implement monetary policy in financial markets transformed by the financial crisis.

After almost two years of effort to keep the fed funds rate, its favoured policy interest rate, from bumping against the top of its target range, the Fed now finds it uncomfortably close to the bottom of the range — at 1.55 per cent, just 5 basis points above the low end.

Having previously cut the interest the Fed pays on banks’ excess reserves — something which acts as a magnet for other short-term rates such as the fed funds rate — the FOMC is expected to raise it on Wednesday by 5 basis points, according to analysts at multiple banks.

“The Fed is worried right now about losing control of fed funds, but to the downside,” said Mr Cabana at Bank of America.

Mr Powell has been at pains to say that none of its actions, in particular the decision to expand reserves held at the Fed, have added up to quantitative easing, the post-crisis stimulus programme in which the Fed expanded its balance sheet with longer-dated Treasuries.

But as the equity markets in the US continued to rise over the past few months, analysts have become sceptical that there is a difference.

“The market mythology has become the stock market can’t go down when the Fed is adding reserves,” said Ian Shepherdson, chief economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics.

When it last met in December, the FOMC signalled that it did not intend to make any changes to interest rates in 2020. According to investor bets compiled by the CME Group, markets see a 90 per cent chance that the fed funds target range will be held at 1.5 to 1.75 per cent on Wednesday.

The Fed will not be publishing a new set of economic projections at this week’s meeting and analysts do not expect a change to the committee’s monetary policy statement.

Source: Economy - ft.com