The surge in government borrowing in all the major advanced economies due to the pandemic has had few precedents, even in wartime. In the US, for example, public borrowing in the quarter from April to June 2020 alone is expected to reach $3tn, almost 15 per cent of this calendar year’s gross domestic product.

The IMF estimates that US government debt will exceed 130 per cent of GDP after the recession, more than 30 percentage points higher than a decade ago. As the world’s largest borrower, the country will no doubt influence how other nations manage their debts, in terms of the quantity and duration of the instruments issued by governments, and any bonds purchased by central banks.

Assuming countries are unwilling to introduce “debt jubilees” to write off their obligations, or swap them into equity, the public debt mountains will need to be managed indefinitely, with little immediate prospect of reducing their size. The larger the scale, the greater the economic costs of debt mismanagement.

So far, markets have been able to absorb the rise in US public debt with few serious hiccups, though the Federal Reserve has injected emergency liquidity to prevent dislocation in longer-term government bond markets.

The government’s need for finance has been met largely through issuing short-dated bills, which have mopped up the rise in household savings driven by unemployment support. In addition, the Fed is resuming its regular programme of debt purchases, in an open-ended manner.

There has been no panic about the sustainability of government debt, either in the US or elsewhere. This is a big success story.

The combination of short-term bill financing plus central bank purchases of longer-dated debt could persist for a long while. However, that is not what happened to debt management in the years following the financial crisis in 2008.

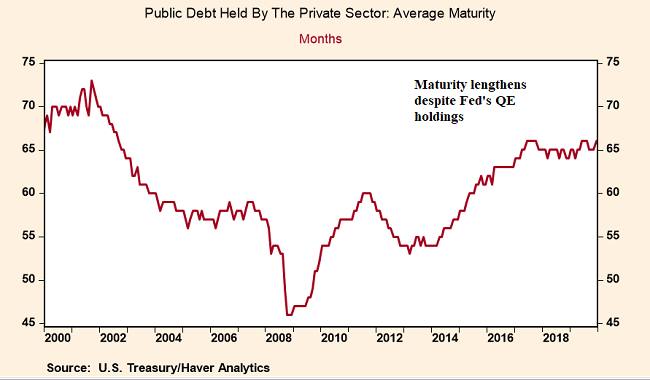

Then, the Treasury initially responded to its higher budget deficit by issuing bills, but that debt was refinanced with much longer duration notes and bonds. This extended the weighted average maturity of market debt from 46 months to 66 months (see box). Recent advice to the Treasury suggests the same thinking might apply this time.

Why does the Treasury generally prefer longer-duration debt? After all, since there is usually a positive “term” premium in long-bond yields, the cost of servicing it is generally higher than the cumulative cost of continuously rolling over those of shorter terms.

History shows that the Treasury can usually reduce service costs markedly with short-dated debt issuance, but only by accepting much greater interest rate risk if inflation or real bond yields suddenly rise sharply. In such circumstances, the need to refinance maturing short-dated debt would quickly lead to a spike in net interest payments, adding to the budget deficit — probably in adverse economic conditions.

A preference for long-dated debt therefore smooths interest rate payments in crises, albeit by raising the average debt service costs over many decades. The Treasury normally errs on the side of taking out this insurance policy, especially when long-term bond yields are abnormally low, as they are now.

The economist John Cochrane argues that bond duration should now be extended very aggressively, since in his opinion the recent surge in debt makes a US fiscal crisis possible in coming years.

But this may make it more difficult for the Fed to ease monetary conditions by purchasing Treasury debt to reduce yields and cut bond duration, as it has done in past periods of quantitative easing.

The outcome in the 2010s was a conflict, in which the Treasury extended the duration of bonds held by the public, while the Fed acted to shorten duration. Estimates suggest that the central bank’s QE reduced 10-year government yields by 1.37 per cent, but the Treasury’s bond issuance eliminated about 60 per cent of this decline.

As the Treasury and the central bank are two parts of a single public sector balance sheet, it makes little sense for them to pull in entirely different directions. If secular stagnation deepens in coming years, as many expect, the Treasury should focus on shorter-term funding to help the Fed reduce bond yields and support economic growth.

Will the Treasury extend the duration of the public debt in the 2020s?

Following precedent, the US government has initially funded an unexpected surge in the budget deficit by relying on the bill market.

Bill issuance reduces the maturity of its overall debt, but the Treasury may consider extending duration in coming years, as it did in 2013-17. This could conflict with the Fed’s monetary policy if secular stagnation persists.