We are now talking real money.

The European Commission has finally unveiled its proposal for a post-coronavirus economic recovery package, the poisoned chalice of a task it was given by national leaders who could not themselves come to an agreement last month. The size of the package is €750bn, raising the €500bn figure proposed by the leaders of France and Germany a week earlier. Gone is the financial wizardry that Brussels excels in: these numbers refer to actual borrowing and spending, not some targeted “mobilisation” of private investment assumed from a sliver of actual committed resources.

My Brussels colleagues explain the details and break down the questions that now have to be addressed to gain the required unanimous support. These include how much of the money should be spent outright rather than lent (the commission foresees about a two-thirds to one-third split), how it should be financed (EU-level taxes or national contributions), conditions for receiving the money and more money for specific causes to buy member states’ support.

Here I want to ask what this package, if something like it survives the negotiations, would and would not achieve.

It would not constitute what many now call a “Hamiltonian moment”, in reference to the first US Treasury secretary’s decision to have the new federal government assume the debts of the individual states. The EU will not assume any national debts at all, the new borrowing it will undertake in its own name will be a one-off and the increase in the EU’s resources will be limited to the minimum necessary to service the debt.

So some federalists will be disappointed. But put it in perspective: they are disappointed that the recovery plan does not achieve something that is not part of its purpose. Indeed, it is precisely the lack of a Hamiltonian leap to permanently greater fiscal integration that gives the plan a fighting chance to gain unanimity.

What it does do is significant enough. First, there should be no quibble that these numbers pack quite a punch. Added to the previous loan-based recovery packages put together by the EU in recent months, member states will have a total of about €1.3tn available in EU-level resources on top of the regular EU budget, about 10 per cent of annual gross domestic product. Even just the latest package would have up to €82bn available for Italy, 4.5 per cent of its annual GDP. Even spread over a few years, these numbers make a macroeconomic difference. True, the economic cost of Covid-19 is much larger and that cost will not be shared equally across the whole EU. But compared with the difference between countries in their economic losses, the common resources are sizeable.

Second, what matters most in the short run is whether the common EU response removes any inhibitions for national governments to do everything it takes to limit the economic harm from Covid-19. By far the biggest budgetary firepower remains at national level, but the fact that some countries’ public finances are more fragile than others could make them pull their punches. The result could be a permanently distorted single market. But with the whole range of recovery funding now being made available — to which we should add colossal bond-buying by the European Central Bank — the only reason for countries not to spend enough is that they decline to avail themselves of what is available. Not making use of a new, virtually conditionless credit line from the European Stability Mechanism rescue fund, for example, is to refuse to take yes for an answer.

Third, there is a lot of emphasis on spending the common resources on areas that align with the EU’s future-looking priorities. This may be rhetoric as much as reality: there is for example more money being put into traditional agricultural spending, too. But the idea is right. European economies already needed to be restructured and future-proofed, and this need is only stronger in a post-pandemic world. So the microeconomics of how the money is spent — focusing it on making economies function better — is at least as important as the macroeconomic size of any cross-country transfers.

Fourth, do not neglect the potential effect on financial markets and corporate financing from these programmes. The recovery plan includes a strand to provide equity financing to companies struggling after the Covid-19 lockdown — at best, this can help push small European companies away from their complete dependence on bank financing and foster a culture of risk capital in the EU. Meanwhile, the borrowing programme envisaged by the commission, which would stretch out repayments until 2058, would create a new pan-European benchmark asset across the entire yield curve. These aspects of the plan could spur on the work to build European capital market and banking unions.

Everyone will find something to dislike in these plans. But it looks like, for once, the good need not be defeated by wishes for the best.

Coronanomics readables

Gavyn Davies warns about soaring savings rates, which could hold back demand in the recovery if they do not come down to pre-coronavirus levels.

Denmark, among the first to close and first to reopen in Europe, demonstrates the benefits of acting early and aggressively against a pandemic.

Spain is the first country to use the crisis to put in place a permanent large-scale reform to change how the economy functions: a new minimum income guarantee should be in place by next month.

In my latest FT column, I argue that we must remember the crucial role the arts play in our lives and in society and accord them special treatment as we design government support.

Numbers news

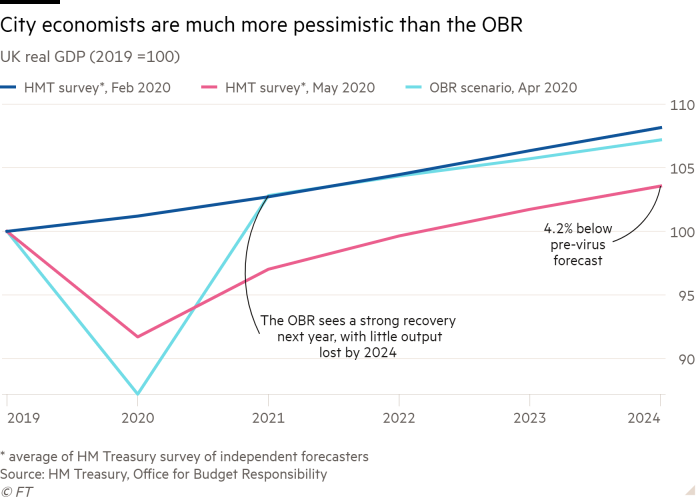

Independent economists forecast that the UK economy will still be 4 per cent smaller than the pre-pandemic trend as far out as 2024. This is much more pessimistic than official forecasters predict, and implies a persistent and large public sector deficit.