Donald Trump has resumed his demands for the “pathetic, slow moving” Federal Reserve to lower rates in the face of the coronavirus, and “Also, stimulate!”

The Fed has, of course, already lowered rates by a surprise half a point, something it had not done since the financial crisis. But it has also been busy since, in ways the US president might not have noticed.

The Fed is now fencing with both hands: having eased monetary policy to support growth, it is now expanding liquidity policy as well — moving extra cash out to banks to make sure financial markets function cleanly through the disruption caused by the outbreak.

Here are five things the Fed could still do.

Keep cutting

Investors have already bet that the Fed will announce another interest rate cut at its next scheduled meeting on March 18. A big one, of three-quarters of a percentage point. That would leave rates just one quarter-point rate cut away from zero, a level not seen since 2015.

Zero looks like a limit. In the minutes of October’s meeting, a rare consensus of “all participants” — every single Fed president and governor — said that negative rates were not a good tool for the US. They had not worked well abroad, they concluded, and would prevent America’s banking sector from lending.

A drop in short-term rates may not be the most useful response to the outbreak anyway. “A rate cut will not reduce the rate of infection. It won’t fix a supply chain,” Jay Powell, Fed chairman, said in his press conference last week. “We get that.”

The most recent cut “certainly is a cushion”, said Nellie Liang, an economist at the Brookings Institution who was the first director of the Fed’s Division of Financial Stability. “But if markets become disrupted, it’s much more important to keep funding and credit flowing than to cut rates another 50 basis points.”

Provide more liquidity to the banking system

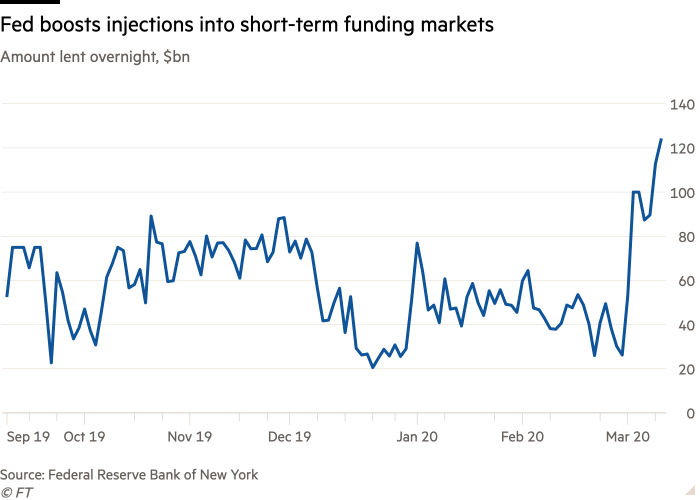

On Monday, after a collapse in oil prices panicked investors, the New York Fed announced it would increase the amount of cash it provides to banks through short-term lending in the repo market, where investors swap high-quality collateral such as Treasuries for cash.

Krishna Guha, vice-chairman at the investment bank Evercore ISI, called it a “baby step”, pushing instead for the Fed to “pull the trigger” on larger liquidity measures. Mr Guha said the central bank should consider offering up three or six-month loans, not just the current overnight and two-week loans being made available.

In 2007, as the financial crisis began to unfold, the Fed established the Term Auction Facility, or TAF, through which it offered one- and three-month cash loans to any bank, not just to its select list of “primary dealers”. The Fed could relaunch it with a simple vote from just its board of governors.

Charles Calomiris, a professor at the Columbia Business School who talks frequently to Fed policymakers, said promising to act might be as good as acting. “We stand ready to make sure markets are functioning in an orderly way”, could be a powerful message if the Fed were to say it, he suggested.

With the US Treasury, provide more liquidity to more institutions

Under section 13 (3) of the Federal Reserve Act, the Board can decide in “unusual and exigent circumstances” to buy “notes, drafts and bills of exchange” — a way to provide funding for financial institutions that are not banks, such as broker-dealers who trade stocks and bonds, which do not have access to the Fed’s other lending facilities.

But these purchases have to be used to shore up the financial system, and they couldn’t be used to prop up failing companies. And they would have to be temporary. The Fed did this during the financial crisis, but Congress tightened up the rules afterwards, mandating that the Fed would have to consult with the Secretary of the Treasury if it wanted to do it again.

Jan Hatzius, chief economist at Goldman Sachs, said such a move was unlikely. “It would probably take a material further deterioration in market conditions and functioning for such facilities to be re-established,” he said in a note.

Roll out QE4

Lael Brainard, Fed governor, endorsed acting early and decisively in a downturn © Bloomberg

In contrast to their aversion to negative rates, policymakers have suggested they would consider fighting any future downturn with another crisis-era tool, quantitative easing, in which they would buy medium- and long-term US government securities — and that they would do so “earlier and more aggressively than in the past”, according to meeting minutes. The Fed used QE three times after the crisis to bring down long-term rates and stimulate the economy.

In a speech in late February, Lael Brainard, a Fed governor, looked back at the financial crisis and concluded that “in some cases around the world, unconventional tools were implemented only after long delays and debate, which sapped confidence, tightened financial conditions, and weakened recovery”. She suggested the Fed not make that mistake.

The Fed does not appear to be ready yet. In his press conference after the surprise cut, Mr Powell said that “in the current context”, the Fed had no plans for monetary policy other than lowering rates.

With Congress, roll out ‘Super QE5’

On Friday, Eric Rosengren, president of the Boston Fed, said that if both policy rates and the yield on 10-year Treasury notes went to zero and stayed there, it would be difficult for either rates or Treasury purchases to have an effect on financial markets. You cannot drag something down when it is already on the floor.

In that case, he said, the Fed might consider buying “a broader range of securities or assets”, as Japan’s central bank has done through purchases of equities.

Mr Rosengren was floating an option well outside anything imagined in the Fed’s current rule book, however, one that would require new legislation from Congress. There is no indication that anyone on Capitol Hill wants to try it yet.

Anyone who remembers what it took to pass and carry out the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill might expect it would take a much bigger crisis for anyone in Washington to consider doing it again.