“Please get ready for the storm to hit — because hit it will,” Mark Schneider, chief executive of Nestlé, the world’s largest food manufacturer, told staff on Monday. “We need to focus our efforts on securing supplies, manufacturing and logistics every step of the way. For those areas that are not affected yet, get prepared by building inventories of critical supplies and products.”

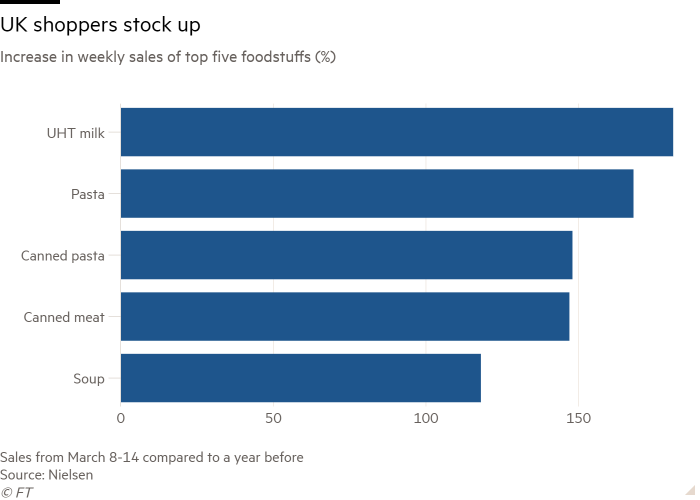

To fill their “pandemic pantries”, consumers have rushed to buy non-perishable staples such as toilet paper, canned goods and pasta — especially pasta. In the UK, for instance, pasta sales spiked 168 per cent in the week to March 14 compared with the year before.

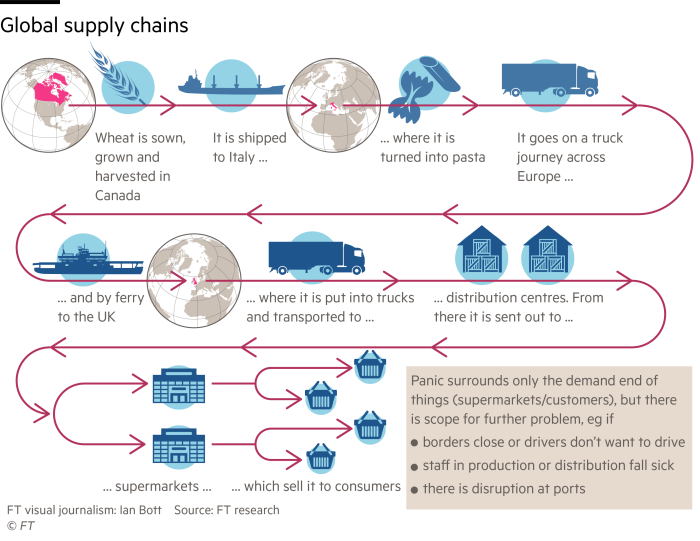

Following the journey of pasta from farm to fork illustrates all the processes that will need to be kept running during the coronavirus outbreak. Like many foodstuffs, pasta relies on a highly complex international supply chain — often passing through several countries on the way to consumers’ plates.

For pasta eaten in the UK, most is made from wheat shipped from Canada, which is then processed by companies such as Barilla and De Cecco in Italy, which exported $3bn of pasta last year. After being transported by trucks through Europe, UK wholesale distributors, such as Princes, will then sell it on to supermarkets.

Wheat production itself should be relatively unaffected by the coronavirus. In Canada, grain production and harvesting is largely mechanical.

“One person can be planting hundreds of acres,” said Chuck Penner, analyst at LeftField Commodity Research in Winnipeg. The wheat is transported to ports by rail and the handling is largely automated.

The price of Canadian durum wheat has risen 8.5 per cent since the start of the year because of the stockpiling-driven pasta demand, according to Mintec, the commodity data group. Nevertheless, at this point, many large food manufacturers hedge against commodity price rises for several months ahead, said Andrew Searle, managing director of consultants AlixPartners.

If port workers in Europe fall sick, however, supplies coming into Italy could be affected; the country imports about half of the 5m-tonnes of durum wheat it uses for pasta each year.

For now, production at Italian factories is running at full capacity compared with the usual 75 per cent, according to Ivano Vacondio, president of Italy’s food and beverage federation, Federalimentare, as producers struggle to meet a doubling in demand. This is despite a 12-15 per cent decline in the factories’ workforce, mainly because of staff’s childcare problems.

“You can imagine the pressure the factories are facing,” said Mr Vacondio, who is also the chairman of a leading Italian flour producer, Molini Industriali. “But things are under control. Factories won’t be closed.”

Even if production can be maintained in Italy, however, analysts warn there may be further disruption ahead if border controls clog motorways, deterring drivers from delivering products. “Food is a priority and things should be moving freely, but no one wants to get caught up in a line of 1,000 trucks,” said Stefan Vogel, analyst at Rabobank.

Governments are also stocking up on staples, with countries including Algeria and Turkey issuing new tenders for wheat, while Kazakhstan has stopped exports of food including onions and buckwheat.

For the UK, a potential pinch point in the food supply chain is the Channel crossing. With more than half of freight from Europe using ferries, the health of the shipping sector could pose a risk, warned Bob Sanguinetti, chief executive of the UK Chamber of Shipping.

Wheat production should be relatively unaffected by coronavirus © Reuters

“The country needs shipping to keep moving for the supermarkets to function,” he said, noting that most ferry operators rely on carrying passengers as well as freight. Passenger traffic has fallen 90 per cent, however, leaving the companies struggling.

Closer to consumers’ plates, distributors are recruiting staff to keep up with surging demand. “We work with one distribution centre handling food products and their labour requirement has trebled over the past two weeks,” said James Mallick, compliance director at the UK food industry recruiters Pro-Force.

Some of that demand may ease as households’ store cupboards are filled, said Mr Mallick, but the shift away from eating out is expected to fuel continued strong demand for retail food products and hence the need for extra workers.

While output of grain may escape the ravages of the coronavirus crisis, it will be in the perishable fruit, vegetable, meat and dairy products where shoppers are likely to see fewer choices if the crisis continues, say analysts and consultants.

The pandemic could disrupt the flow of fruit and vegetables to households as labour-intensive planting and harvesting could be disrupted by immigration restrictions.

Apart from potential labour shortages affecting harvesting and picking, the crisis could hit transport such as shipping and flights. Products from other continents such as some exotic fruits could be in short supply but also produce consumers expect to eat regularly such as avocados, mangetout and baby courgettes.

“There may be certain fruits and vegetables that will be impacted,” said David Howorth, executive director of UK supply chain consultants Scala, who notes that the industrial food manufacturing supply chains are more robust.

For the UK, with 90 per cent of the food we consume produced domestically or in Europe, there is unlikely to be an issue of having food on the table. However, for the remaining 10 per cent, “there may be some reduction in the range of food that we are normally used to,” he said.

This will apply to an extent even in less import-dependent countries such as the US: despite its large domestic agricultural sector, the country imports more than half of its fresh fruit, for example.

For now, there are no problems with overall supply, while companies along the chain are frantically adapting their operations to meet demand.

“People will get their pasta,” said Mr Vacondio in Italy. “For the moment they are producing, they are packaging and they are shipping . . . of course we don’t know what’s going to happen in a month. It’s difficult to predict.”